We preach the gospel that tabletop matters, often referring to the aesthetic, quality, and flexibility of products. However, a key element easily overlooked is how the forks, plates, and glassware can directly affect how food tastes. Our U.K. correspondent Isaac Parham recently had a chance to sit down with Charles Spence, author of Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating to figure out how exactly something as simple as a fork can change the way people taste food.

When Charles Spence talks tabletop one is inclined to listen.A Nobel Prize winner, Oxford University professor and prolific author, this eminent ‘gastrophysicist’ is redefining our understanding of flavour and how it is shaped by every element of the dining experience. And, yes, that very much includes tabletop. Over the course of our hour-long chat in an Oxford pub close to his lab, Spence riffs on the past, present, and future of tabletop. We cover cutlery weight, eating with your hands, and coloured plates. Unsurprisingly, he makes fascinating company.

TabletopJournal: Charles, firstly, I’m keen to understand how you arrived at this area of study?

Charles Spence: I’d always been interested in the senses. I started with hearing and vision – then I added touch. Then when I came back here (Oxford University) twenty years ago, Unilever were here in the audience for a conference. They said we’re doing something similar – we’ll fund you. Then we started super gluing things onto people’s tongues to do taste and before you know it you’re doing flavour things.

I’d always thought flavour was too messy – much easier to stick with things on a computer. Then in 2000 I was doing something on iced teas and fruit teas that looked beautiful, smelt beautiful but were just disappointing when you tasted them. At the same time doing another project with Unilever on clothing, how to make things feel different by making them sound different. That became the Sonic Chip experiment, that by changing the sound — the crunch of a potato chip — you can change its freshness, crispness, its likability.

Then it exploded in interest with the Nobel Prize in 2008 for nutrition, that helped to elevate it.

TJ: And that brought you into the food world?

CS: Yes, well I was already working with Firmenich flavour house in Switzerland who were working with Heston (Blumenthal) making olive oil jelly or ice cream; they put us together. He came to try the Sonic Chip, that loaded into his Sound of the Sea dish (which sees diners asked to wear headphones while they eat seafood) which led into more experiments with them and chefs that have been through there.

That was that. There was no-one in the food science world doing it exactly; there are food scientists but they do the boring feeding chickens and frozen Brussels sprouts, this side of it has never been touched by the psychological scientists. It just sort of seemed right after three decades of modernist cuisine.

TJ: And your experiments at the lab: am I right in thinking chefs like Heston take your results and apply them to their own menus?

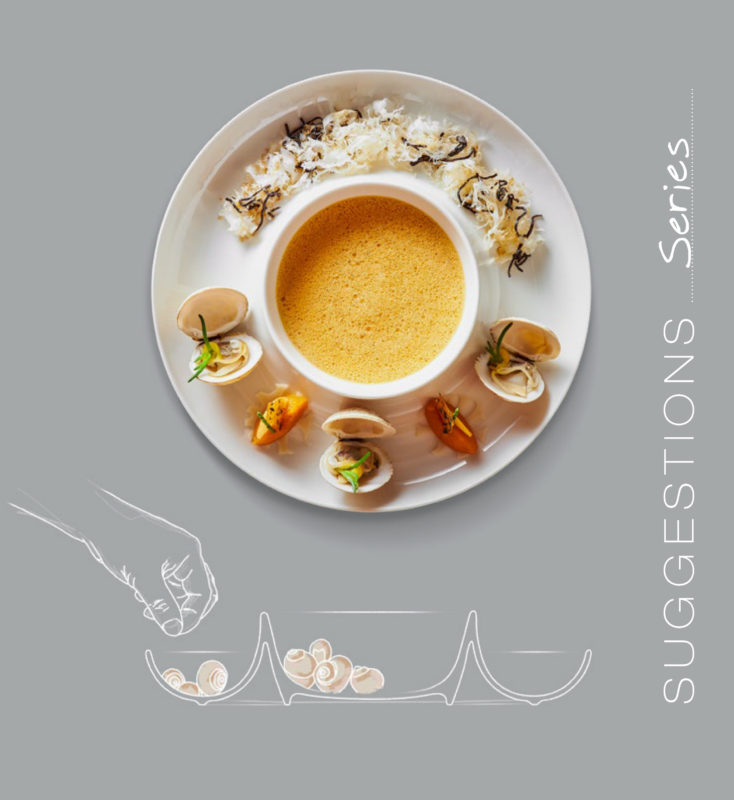

Yes. Some things don’t catch on but there are others that do. We did something about tastes and colours, because tastes have colours; colours have taste. White is salty, black is bitter, pinky/red is sweet. And then you can see that in a dish, with spherification. It’s brought to diners in random colours on these colour spoons and then that becomes the experiment. Waitresses can note from the way people arrange their spoons which one they think is salty, sour, sweet. And then that goes into a paper and it moves round the world as different chefs do their own riff on it with local ingredients.

TJ: On the subject of colours: if I serve something on red plate, and something on a white plate, what’s going to be the difference in terms of flavour?

CS: So for the red one, it would be the easiest to say that what you put on that plate is unhealthy — or perceived as unhealthy — so crisps, or snacks or chocolates or white bread, people will tend to eat less. If it’s healthy food it probably won’t make much difference but unhealthy foods – you see the red plate and there’s some kind of aversion or worry or whatever. That’s three or four studies around the world that show that. Does that mean that it tastes different to you or changes your behaviour? It certainly could change the taste, I know if I change the room lighting and give you a white and a black tasting glass it will change the taste.

TJ: And to what extent do you think that chefs know these rules instinctively?

CS: There is an element of it being the science of the bleeding obvious! Sometimes it’s kind of true but it’s still useful, but other times it’s not. Recently I was in New York with Jehangir Mehta from Graffiti and he was saying that in his training he was told odd numbers on a plate instead of even – lots of chefs believe that.

TJ: That’s not true?!

CS: No. At least not in Western diners. We were hoping it was going to be true but it’s not true. We tested five thousand people, seared scallops on a plate three or four – and it turned out it had no effect at all, honours even. If you say which one do you prefer, people obviously go for the one with the most.

On the other hand, it could be something like going to Fat Duck, talking to them about the weight of the cutlery they have there (research has shown that, generally, the heavier the cutlery, the better a dish tastes). They say, “Oh, intuitively I kind of know that” and certain restaurateurs although they intuitively know it they don’t put any weight in it. So by measuring it you can say on average adding 100g cutlery weight increases willingness to pay by x percent, then they can figure out if it’s worth that and make informed decisions. So it can go both ways.

TJ: Let’s talk cutlery in more detail. You mention in your new book (Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating) that you think we are very conservative when it comes to cutlery. How do you think it evolving?

CS: On the one hand it’s going to be more eating with the hands. That’s been happening at The Fat Duck and Noma, the first three, four, five courses all eaten with your fingers – finger food. Then Mugaritz are going to go wholly finger food as of this season, twenty courses or something and it is all sort of sharing. It’s sort of prehistoric – there’s a stone shard of meat that anchors the whole thing. But otherwise it’s all fingers and wiping with moist towels. So we’re going to see more of that. It’s going to become more acceptable, as dining gets less formal that sort of fits in there.

On the other hand, there are some foods that just don’t lend themselves to finger-eating. Risotto and stuff. The evolution of cutlery… and you see that happening already, is it a plate or is it cutlery? It’s kind of blurring the boundary there. Fat Duck now are doing heavy furry spoons for the last course of Counting Sheep. Studio William up in the Cotswolds are doing the dimpled spoons, things like that. Ten years from now we’ll look back and say, “Why did we never think of that?”

TJ: Yes, we’ve got to the point where a few restaurants have different plateware for different courses but cutlery stays the same throughout…

CS: We’re getting a bit closer. There are practical reasons. Although the cost per unit of a new plate at The Fat Duck could be hundreds or thousands of pounds a piece and cutlery I guess would be less than that, so it would be easier to have a new knife and fork and less breakable!

I suspect the difference is it’s much easier to find a designer or plateware manufacturer, much harder to find someone who’s going to give you something truly innovative in terms of cutlery.

TJ: What are the common gastrophysical mistakes made by restaurants?

CS: The cutlery is one… it costs money of course, but if you knew how much it enhances the experience you would do better on that.

Certainly music. Potentially simplish to address but not thought about at all. It’s a bit trial and error, – it depends a bit on what you want to get out. Is it about just maximising sales? Or shifting people’s purchasing options up, or enhancing what they taste? Perhaps it’s easier for the bigger chains to systematically address.

Menu design I think. There are experts, or self proclaimed experts you might think, who are giving restaurants advice on that. If you were printing it daily, weekly or whatever, why wouldn’t you play with that a bit?

By Isaac Parham